history of slavery in the americas

Author's Note: It is impossible to to give a full account of slavery or the history of race in the United States and Rhode Island here. I have also not included the history of Cape Verdeans, indigenous peoples, and Asians in Rhode Island. These discussions, while critically important, are far beyond the scope of these pages. For an excellent detailed discussion of the topics below, visit EnCompass: A Digital Archive of Rhode Island History. Rhode Island Historical Society and Providence College or visit the John Carter Brown Library's pages on slavery in Rhode Island.

Slavery in America began in the early 17th Century and continued to be practiced for the next 250 years by the colonies and states. Slaves, mostly from Africa, worked in the production of tobacco crops and later, cotton. With the invention of the cotton gin in 1793 along with the growing demand for the product in Europe, the use of slaves in the South became a foundation of their economy.

Race and slavery in Rhode Island

As early as 1638, Rhode Islanders were transporting enslaved Native Americans to Bermuda. By the end of the century Rhode Island had become the only New England colony to use the enslaved for both labor and trade. After overtaking Boston by 1750, Newport and Bristol were the major slave markets in the American colonies. Slave-based economies existed in the Narragansett plantation family, the Middletown crop workers, and the indentured and enslaved craftsmen of Newport.

By the mid-18th century, 114 years after Roger Williams founded the tiny Colony of Rhode Island, the enslaved lived in every port and village. In 1755, 11.5 percent of all Rhode Islanders, or about 4,700 people, were black, nearly all of them enslaved. In Newport, Bristol and Providence, the slave economy provided thousands of jobs for captains, seamen, coopers, sail makers, dock workers, and shop owners, and helped merchants build banks, wharves and mansions.

By the mid-18th century, 114 years after Roger Williams founded the tiny Colony of Rhode Island, the enslaved lived in every port and village. In 1755, 11.5 percent of all Rhode Islanders, or about 4,700 people, were black, nearly all of them enslaved. In Newport, Bristol and Providence, the slave economy provided thousands of jobs for captains, seamen, coopers, sail makers, dock workers, and shop owners, and helped merchants build banks, wharves and mansions.

|

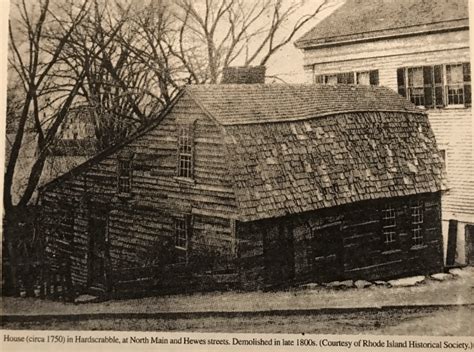

Hard Scrabble and Snow Town Riots

Hard Scrabble was a predominantly black neighborhood in northwestern Providence in the early 19th century. Away from the town center, its inexpensive rents attracted working class free blacks, poor people of all races and marginalized businesses such as saloons and houses of prostitution. Tensions developed between the residents of Hard Scrabble and other residents of Providence. Hard Scrabble was one of several similar neighborhoods in urban centers in the Northeast where free blacks gathered to further themselves socially and economically. Other African American communities created in cities with growing job markets in the same time period include the northern slope of Boston’s Beacon Hill, Little Liberia in Bridgeport, Connecticut and Sandy Ground on New York’s Staten Island. |

On October 18, 1824, a white mob attacked black homes in Hard Scrabble, after a black man refused to get off the sidewalk when approached by some whites. Although the mob claimed to be targeting places of ill-repute, it destroyed buildings indiscriminately. Hundreds of whites destroyed approximately 20 black homes. Four people were tried for rioting, but only one was found guilty.

After the Hard Scrabble riot, the Snow Town neighborhood rose in roughly the same area. It was another interracial neighborhood where free blacks and poor whites lived among crime and marginal businesses. In 1831 more riots took place in Snow Town, one triggered by the shooting death of a sailor. Once again, the mob destroyed many homes, targeting black homes even though the people living in them had no apparent ties to the shooting, spilling over into nearby Olney Street. This time, the militia was called out, and it killed four white rioters.

The Hardscrabble Riot had engendered little media sympathy for its victims. But by the time of the Snow Town riot, leading citizens and journalists took the problem far more seriously. After the Snow Town riot, written opinion approved of suppressing rioters to maintain order, and Providence voters approved a charter for a city government containing strong police powers.

After the Hard Scrabble riot, the Snow Town neighborhood rose in roughly the same area. It was another interracial neighborhood where free blacks and poor whites lived among crime and marginal businesses. In 1831 more riots took place in Snow Town, one triggered by the shooting death of a sailor. Once again, the mob destroyed many homes, targeting black homes even though the people living in them had no apparent ties to the shooting, spilling over into nearby Olney Street. This time, the militia was called out, and it killed four white rioters.

The Hardscrabble Riot had engendered little media sympathy for its victims. But by the time of the Snow Town riot, leading citizens and journalists took the problem far more seriously. After the Snow Town riot, written opinion approved of suppressing rioters to maintain order, and Providence voters approved a charter for a city government containing strong police powers.

|

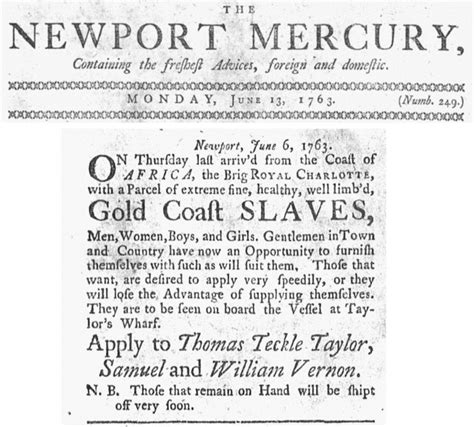

Rhode Island Slave Trade Rhode Island was the undisputed leader in the slave trade among the colonies. Between 1709 and 1807, Rhode Island merchants sponsored at least 934 slaving voyages to the coast of Africa and carried an estimated 106,544 enslaved to the New World. Newport, the colony's leading slave port, took an estimated 59,070 enslaved to America before the Revolution. In the 54 years between 1709 and 1775, over 59,067 enslaved people were transported and sold by RI slavers or an average of 1,094 enslaved persons per year primarily in the Caribbean. Almost all of the ships claimed Newport as their home port. During this time, the average enslaved person cost about 88 gallons of rum. Rhode Island rum was the preferred medium of exchange throughout coastal Africa. In the 31 years between 1784 and 1807, over 47,477 enslaved people were transported |

and sold by RI slavers or an average of 1,532 enslaved persons per year. Almost 500 more per year than prior to the Revolution. The average enslaved person cost about 118 gallons of rum. The RI slave trade was shut down between 1776 and 1783. Between 1784 and 1807, Newport still sent out the most slavers with 170 ships, then Bristol with 157, then Providence with 144, and Warren with 31 ships.

Principal RI slave traders were the D'Wolf family out of Bristol with 88 voyages, Briggs & Gardner based in Newport with 22 voyages, Clarke & Clarke from Newport with 22 voyages, Cyprian Sterry from Providence with 17 voyages, Vernon & Vernon from Newport with 10 voyages, Jeremiah Ingraham from Bristol with 10 voyages, and Bourn & Wardwell out of Bristol with 9 voyages. In South County, the plantations with the largest enslaved populations were owned by the Stanton family in Westerly, the Updike family in North Kingstown, the Robinson family from Boston Neck, and the Hazard family from Wakefield. The Brown family, one of the great mercantile families of colonial America, were Rhode Island slave traders. At least six of them -- James and his brother Obadiah, and James's four sons, Nicholas, John, Joseph, and Moses -- ran one of the biggest slave-trading businesses in New England.

Race, Slavery, and the Law in Rhode Island

Rhode Island established the first law regulating slavery on May 18, 1652, as part of the Acts and Orders of the General Court of Warwick. It stated that the blacks or whites forced to serve another must be freed after 10 years after arrival in Rhode Island. The fine for noncompliance was 40 pounds. The law was evidently never enforced, because enslaved Africans were in the Colony that same year. The 1652 municipal law was superseded by a 1703 race-based law passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly that legally recognized black and Native American slavery and whites as their owners. A 1704 law forbade enslaved people to be out after 9 pm on penalty of whipping and made entertaining them a crime.

Rhode Island’s slave laws were the harshest in New England. The runaway law of 1714 penalized ferrymen who carried slaves out of the colony without authorization from their masters. The law against thefts by slaves carried a sentence that could be 15 lashes or banishment from the colony—a particularly dreaded punishment, because it usually meant deportation and sale to the merciless sugar plantations in the West Indies. Statutes were passed in 1728, 1765, and 1775 to curb individual manumissions by requiring the owners or the enslaved individuals themselves to post bond. The bond would be used to support those who had been freed in the event that they could not support themselves and became indigent, or dependent on public aid to survive.

The town of South Kingstown had perhaps the harshest local slave control laws in New England. After 1718, if any black slave was caught in the cottage of a free black person, both were whipped. After 1750, anyone who sold so much as a cup of hard cider to a black slave faced a harsh fine of 30 pounds. A 1751 law extended the entertainment ban to “Indian, Negro, or Mulatto servants or slaves” and explicitly outlawed selling them liquor. The following year, an act was passed to break up “disorderly” homes of people of color.[9] To prevent sea captains from luring African slaves, who apparently made exceptionally good mariners, onto their boats to become crew members, a 1757 law made carrying enslaved people out of the colony without the consent of their masters a crime punishable by a fine of £26. In 1774, the state assembly passed a law making it illegal for any Rhode Island citizen to bring enslaved persons into the colony unless they posted bond to bring them out again within one year. A critical shortage of troops caused the RI legislature in 1778 to pass a bill permitting enslaved men to enlist in exchange for soldiers’ benefits and freedom after at least three years of service; their owners would be compensated for their value up to £120 and would no longer be liable for the support of their former slaves if they were to become indigent after the war.

In 1783, noting that slavery was incompatible with the “Rights of Man,” the legislature passed a post nati (after birth) emancipation bill making all children born to enslaved women after March 1, 1784, free at 18 years of age if female and 21 years of age if male. The original bill required the towns to support these children until they reached the age of freedom, with the assumption that the towns would recuperate the expense by binding them out to service. But the towns objected strenuously, and the bill was amended only eight months later to give the owners of the enslaved mothers of newborns responsibility for their support—and, more importantly, entitlement to their labor—until they reached the age of maturity and were thus eligible for manumission. The day after the bill went into effect, what had changed? Enslaved people remained enslaved. Children born to enslaved women would not be free for nearly twenty years. The only real, immediate change inaugurated by the 1784 bill was to provide an incentive for individual manumission by relieving owners who freed enslaved people between twenty-one and forty (amended by the end of the year to thirty) years of age of further financial responsibility for them, should they become indigent.

In 1783, Moses Brown and other Quakers began to petition for the abolition of slavery in Rhode Island. After a difficult battle, the General Assembly passed the Gradual Emancipation Act of March 1, 1784. It stated that children born to slaves after that date would be free after reaching the age of 21 for boys and 18 for girls. All slaves born before 1784 would remain slaves for life. In the 1790 federal census, there were still more than 260 slaves in Newport. This gradual emancipation was due in large part to the performance of slave and free African members of the First Rhode Island Regiment, who had distinguished themselves during the American Revolution.

After the passage of the national Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required northerners to aid in the re-enslavement of self-emancipated people, the Rhode Island African-American community held a “public mass meeting” at Hoppin’s Hall in downtown Providence. Some of the attendees were free Blacks, who were married to, or friends of, co-workers, and neighbors of, self-emancipated persons. Others had themselves fled to the state, perhaps years before, and were settled with businesses, jobs and families. The parents and grandparents of some may have been enslaved in Rhode Island or elsewhere before gradual emancipation brought about the end of legalized slavery in the state in 1843. They vowed to “pledge to sacrifice our lives and our all” to protect their families and fellow sufferers from consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The men and women resolved that they “believe it to be our duty to God, ourselves, our children, and three millions of our brethren that are in bonds at any hour of day or night, that a slaveholder, or his agent, shall come within the limits of the State of Rhode Island for the purpose of retaking runaway slaves that we will use every means that nature or art may place into our hands to deprive him of his object.” Their final resolution was “that we who have escaped from chains, fetters and the slave driver’s lash, are determined never to go back again, but have adopted the inestimable motto—Liberty or Death.”

Rhode Island established the first law regulating slavery on May 18, 1652, as part of the Acts and Orders of the General Court of Warwick. It stated that the blacks or whites forced to serve another must be freed after 10 years after arrival in Rhode Island. The fine for noncompliance was 40 pounds. The law was evidently never enforced, because enslaved Africans were in the Colony that same year. The 1652 municipal law was superseded by a 1703 race-based law passed by the Rhode Island General Assembly that legally recognized black and Native American slavery and whites as their owners. A 1704 law forbade enslaved people to be out after 9 pm on penalty of whipping and made entertaining them a crime.

Rhode Island’s slave laws were the harshest in New England. The runaway law of 1714 penalized ferrymen who carried slaves out of the colony without authorization from their masters. The law against thefts by slaves carried a sentence that could be 15 lashes or banishment from the colony—a particularly dreaded punishment, because it usually meant deportation and sale to the merciless sugar plantations in the West Indies. Statutes were passed in 1728, 1765, and 1775 to curb individual manumissions by requiring the owners or the enslaved individuals themselves to post bond. The bond would be used to support those who had been freed in the event that they could not support themselves and became indigent, or dependent on public aid to survive.

The town of South Kingstown had perhaps the harshest local slave control laws in New England. After 1718, if any black slave was caught in the cottage of a free black person, both were whipped. After 1750, anyone who sold so much as a cup of hard cider to a black slave faced a harsh fine of 30 pounds. A 1751 law extended the entertainment ban to “Indian, Negro, or Mulatto servants or slaves” and explicitly outlawed selling them liquor. The following year, an act was passed to break up “disorderly” homes of people of color.[9] To prevent sea captains from luring African slaves, who apparently made exceptionally good mariners, onto their boats to become crew members, a 1757 law made carrying enslaved people out of the colony without the consent of their masters a crime punishable by a fine of £26. In 1774, the state assembly passed a law making it illegal for any Rhode Island citizen to bring enslaved persons into the colony unless they posted bond to bring them out again within one year. A critical shortage of troops caused the RI legislature in 1778 to pass a bill permitting enslaved men to enlist in exchange for soldiers’ benefits and freedom after at least three years of service; their owners would be compensated for their value up to £120 and would no longer be liable for the support of their former slaves if they were to become indigent after the war.

In 1783, noting that slavery was incompatible with the “Rights of Man,” the legislature passed a post nati (after birth) emancipation bill making all children born to enslaved women after March 1, 1784, free at 18 years of age if female and 21 years of age if male. The original bill required the towns to support these children until they reached the age of freedom, with the assumption that the towns would recuperate the expense by binding them out to service. But the towns objected strenuously, and the bill was amended only eight months later to give the owners of the enslaved mothers of newborns responsibility for their support—and, more importantly, entitlement to their labor—until they reached the age of maturity and were thus eligible for manumission. The day after the bill went into effect, what had changed? Enslaved people remained enslaved. Children born to enslaved women would not be free for nearly twenty years. The only real, immediate change inaugurated by the 1784 bill was to provide an incentive for individual manumission by relieving owners who freed enslaved people between twenty-one and forty (amended by the end of the year to thirty) years of age of further financial responsibility for them, should they become indigent.

In 1783, Moses Brown and other Quakers began to petition for the abolition of slavery in Rhode Island. After a difficult battle, the General Assembly passed the Gradual Emancipation Act of March 1, 1784. It stated that children born to slaves after that date would be free after reaching the age of 21 for boys and 18 for girls. All slaves born before 1784 would remain slaves for life. In the 1790 federal census, there were still more than 260 slaves in Newport. This gradual emancipation was due in large part to the performance of slave and free African members of the First Rhode Island Regiment, who had distinguished themselves during the American Revolution.

After the passage of the national Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required northerners to aid in the re-enslavement of self-emancipated people, the Rhode Island African-American community held a “public mass meeting” at Hoppin’s Hall in downtown Providence. Some of the attendees were free Blacks, who were married to, or friends of, co-workers, and neighbors of, self-emancipated persons. Others had themselves fled to the state, perhaps years before, and were settled with businesses, jobs and families. The parents and grandparents of some may have been enslaved in Rhode Island or elsewhere before gradual emancipation brought about the end of legalized slavery in the state in 1843. They vowed to “pledge to sacrifice our lives and our all” to protect their families and fellow sufferers from consequences of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The men and women resolved that they “believe it to be our duty to God, ourselves, our children, and three millions of our brethren that are in bonds at any hour of day or night, that a slaveholder, or his agent, shall come within the limits of the State of Rhode Island for the purpose of retaking runaway slaves that we will use every means that nature or art may place into our hands to deprive him of his object.” Their final resolution was “that we who have escaped from chains, fetters and the slave driver’s lash, are determined never to go back again, but have adopted the inestimable motto—Liberty or Death.”

Adapted from material from the Slavery and Justice Exhibition at the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University and material from EnCompass: A Digital Archive of Rhode Island History. Rhode Island Historical Society and Providence College, 2016–2022.