World War One - the war to end all wars

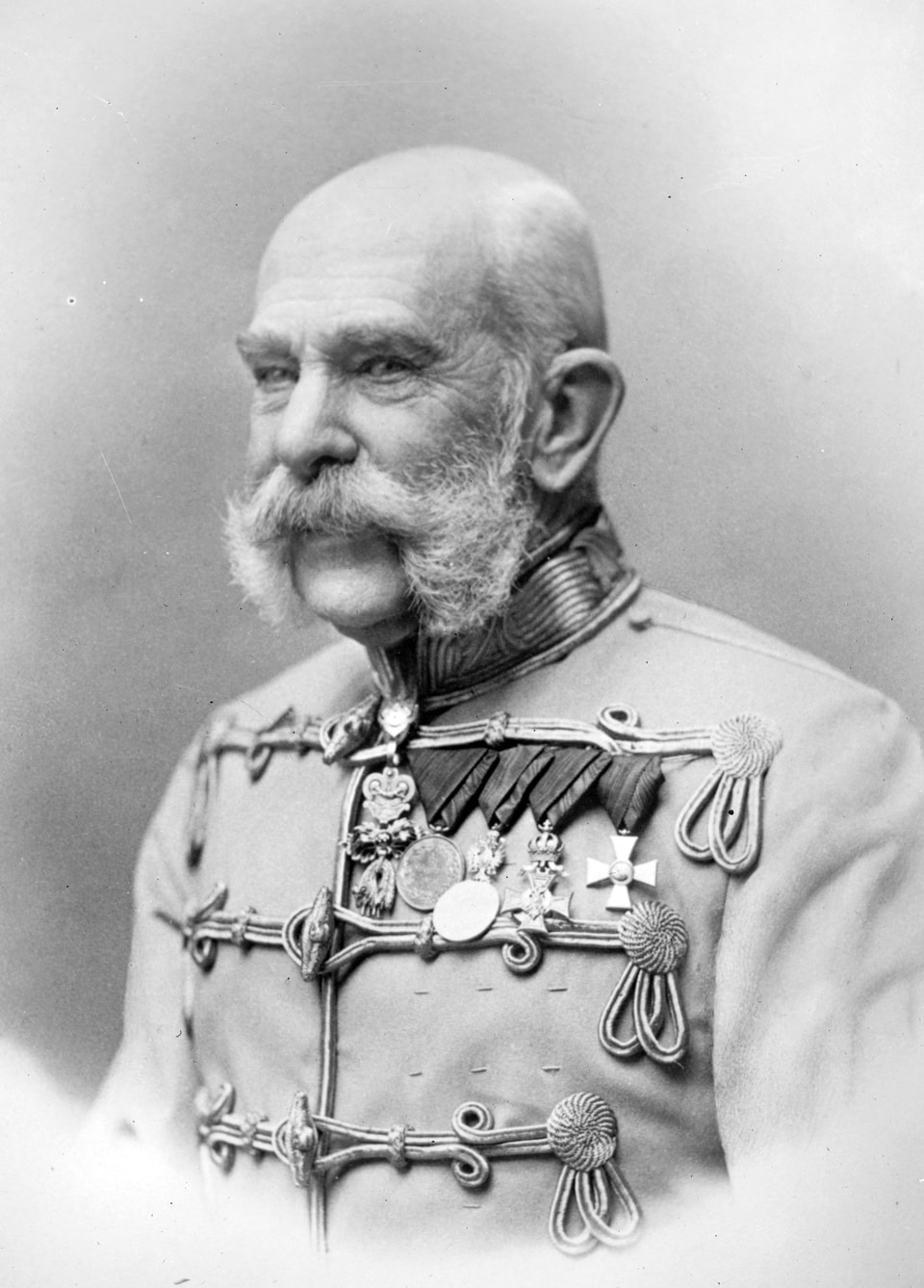

World War I began in 1914 after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and lasted until 1918. During the conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Japan and the United States (the Allied Powers).

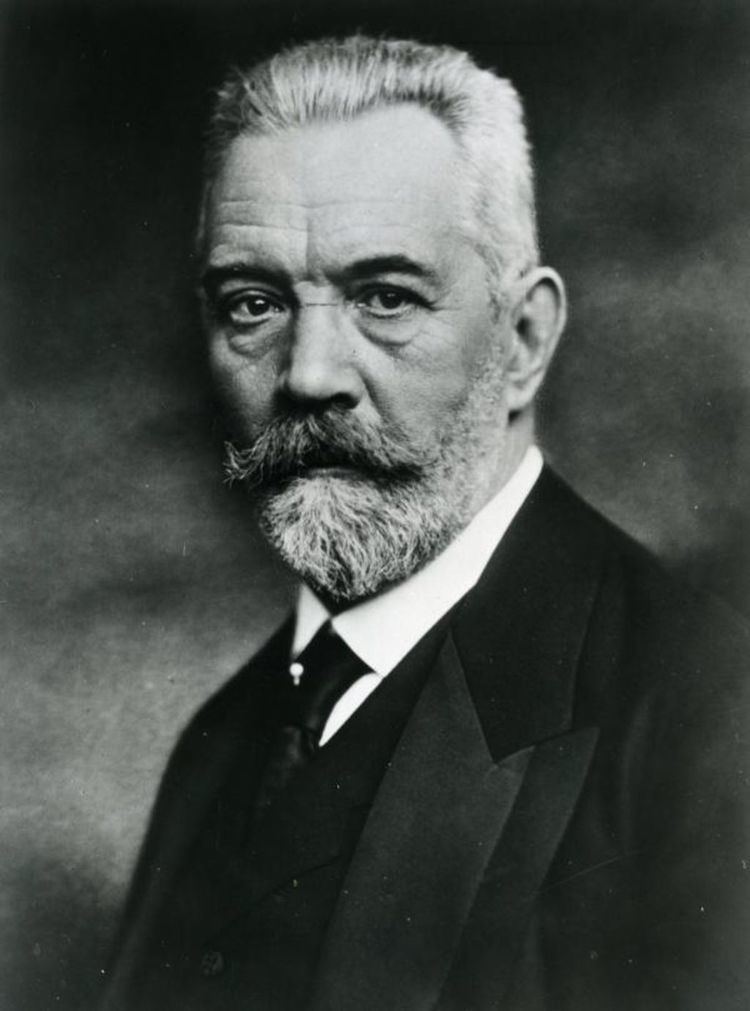

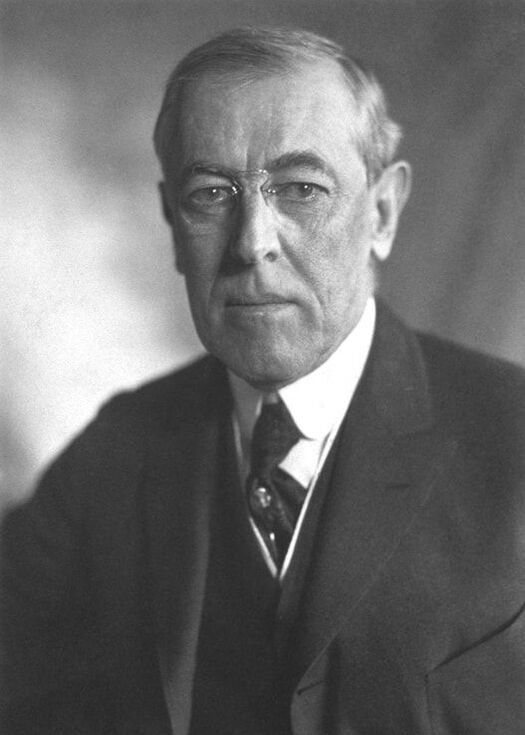

Key Historical Figures of World War One

|

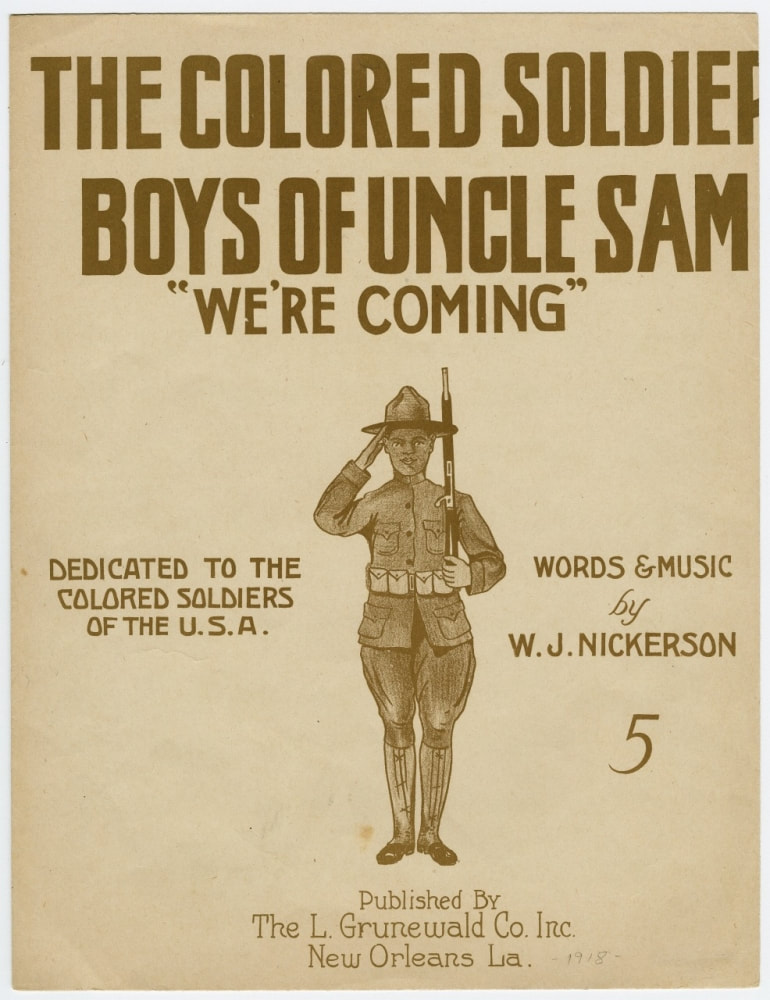

African Americans and World War I

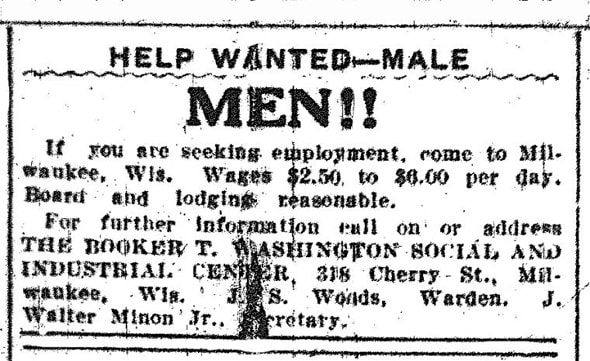

by Chad Williams, Hamilton College World War I was a transformative moment in African-American history. What began as a seemingly distant European conflict soon became an event with revolutionary implications for the social, economic, and political future of black people. The war directly impacted all African Americans, male and female, northerner and southerner, soldier and civilian. Migration, military service, racial violence, and political protest combined to make the war years one of the most dynamic periods of the African-American experience. Black people contested the boundaries of American democracy, demanded their rights as American citizens, and asserted their very humanity in ways both subtle and dramatic. Recognizing the significance of World War I is essential to developing a full understanding of modern African-American history and the struggle for black freedom. |

When war erupted in Europe in August 1914, most Americans, African Americans included, saw no reason for the United States to become involved. This sentiment strengthened as war between the German-led Central Powers and the Allied nations of France, Great Britain, and Russia ground to a stalemate and the death toll increased dramatically. The black press sided with France, because of its purported commitment to racial equality, and chronicled the exploits of colonial African soldiers serving in the French army. Nevertheless, African Americans viewed the bloodshed and destruction occurring overseas as far removed from the immediacies of their everyday lives.

|

By early 1917, the clouds of war had reached American shores. President Woodrow Wilson initially pledged to keep the country out of the conflict, arguing that the United States had nothing to gain from involving itself in the European chaos. Wilson won reelection in 1916 on a campaign of neutrality, but a series of provocations gradually changed his position. Germany resumed unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic Ocean and sank several vessels carrying American passengers. On March 1, 1917, the Zimmermann Telegram, in which Germany encouraged Mexico to enter the war on the side of the Central Powers, became public and enflamed pro-war sentiments. Wilson felt compelled to act, and on April 2, 1917, he stood before Congress and issued a declaration of war against Germany. "The world must be made safe for democracy," he boldly stated, framing the war effort as a crusade to secure the rights of democracy and self-determination on a global scale.

|

These words immediately resonated with many African Americans, who viewed the war as an opportunity to bring about true democracy in the United States. It would be insincere, many black people argued, for the United States to fight for democracy in Europe while African Americans remained second-class citizens. "If America truly understands the functions of democracy and justice, she must know that she must begin to promote democracy and justice at home first of all," Arthur Shaw of New York proclaimed. The black press used Wilson's pronouncement to frame the war as a struggle for African American civil rights. "Let us have a real democracy for the United States and then we can advise a house cleaning over on the other side of the water," the Baltimore Afro-American asserted. For African Americans, the war became a crucial test of America's commitment to the ideal of democracy and the rights of citizenship for all people, regardless of race.

|

The United States government mobilized the entire nation for war, and African Americans were expected to do their part. The military instituted a draft in order to create an army capable of winning the war. The government demanded "100% Americanism" and used the June 1917 Espionage Act and the May 1918 Sedition Act to crack down on dissent. Large segments of the black population, however, remained hesitant to support a cause they deemed hypocritical. A small but vocal number of African Americans explicitly opposed black participation in the war. A. Philip Randolph and Chandler Owen, editors of the radical socialist newspaper The Messenger, openly encouraged African Americans to resist military service and, as a result, were closely monitored by federal intelligence agents. Many other African Americans viewed the war apathetically and found ways to avoid military service. As a black resident from Harlem quipped, "The Germans ain't done nothin' to me, and if they have, I forgive 'em."

Most African Americans nevertheless saw the war as an opportunity to demonstrate their patriotism and their place as equal citizens in the nation. Black political leaders believed that if the race sacrificed for the war effort, the government would have no choice but to reward them with greater civil rights. "Colored folks should be patriotic," the Richmond Planet insisted. "Do not let us be chargeable with being disloyal to the flag." Black men and women for the most part approached the war with a sense of civic duty. Over one million African Americans responded to their draft calls, and roughly 370,000 black men were inducted into the army. Charles Brodnax, a farmer from Virginia recalled, "I felt that I belonged to the Government of my country and should answer to the call and obey the orders in defense of Democracy."

|

Portions of this unit are based on work done by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.