a segregated military

|

Racial violence tested blacks' patriotic resolve. On July 2, 1917, in East St. Louis, tensions between black and white workers sparked a bloody four-day riot that left upwards of 125 black residents dead and the nation shocked. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) responded by holding a Silent Protest Parade in New York City on July 28, 1917. Eight thousand marchers, the men dressed in black and the women and children in white, solemnly advanced down Fifth Avenue to the sound of muffled drums and holding signs such as the one that read, Mr. President, why not make America safe for democracy.

Violence erupted again the following month in Houston, Texas. Black soldiers of the 3rd Battalion of the 24th Infantry, stationed at Camp Logan, had grown increasingly tired of racial discrimination and abuse from Houston's white residents and from the police in particular. On the night of August 23, 1917, the soldiers retaliated by marching on the city and killing sixteen white civilians and law enforcement personnel. Four black soldiers died as well. The Houston rebellion shocked the nation and encouraged white southern politicians to oppose the future training of black soldiers in the South. Three military court-martial proceedings convicted 110 soldiers. Sixty-three received life sentences and thirteen were hung without due process. The army buried their bodies in unmarked graves.

Despite the bloodshed at Houston, the black press and civil rights organizations like the NAACP insisted that African Americans should receive the opportunity to serve as soldiers and fight in the war. Joel Spingarn, a former chairman of the NAACP, worked to establish an officers' training camp for black candidates. "All of you cannot be leaders," he stated, "but those of you who have the capacity for leadership must be given an opportunity to test and display it." The black press vigorously debated the merits of a Jim Crow camp. W. E. B. Du Bois, the noted scholar, editor of the NAACP's journal The Crisis, and a close friend of Spingarn, supported the camp as a crucible of "talented tenth" black leadership, manhood, and patriotism. Black college students, particularly those at historically black institutions, were the driving force behind the camp. Howard University established the Central Committee of Negro College Men and recruited potential candidates from college campuses and black communities throughout the country. The camp opened on June 18, 1917, in Des Moines, Iowa, with 1,250 aspiring black officer candidates. At the close of the camp on October 17, 1917, 639 men received commissions, a historical first.

|

|

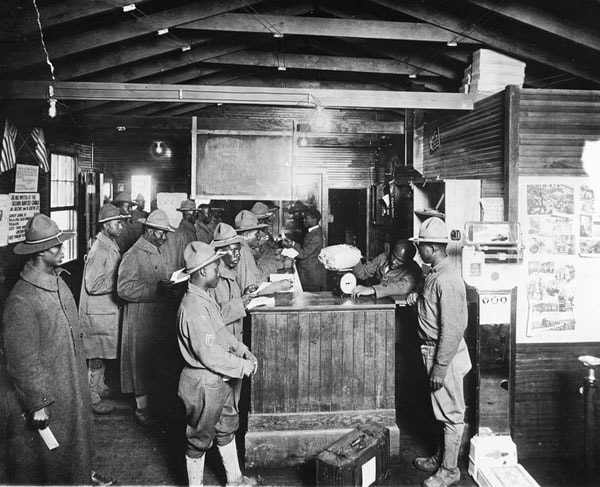

The military created two combat divisions for African Americans. One, the 92nd Division, was composed of draftees and officers. The second, the 93rd Division, was made up of mostly National Guard units from New York, Chicago, Washington, D.C., Cleveland, and Massachusetts. The army, however, assigned the vast majority of soldiers to service units, reflecting a belief that black men were more suited for manual labor than combat duty. Black soldiers were stationed and trained throughout the country, although most facilities were located in the South. They had to endure racial segregation and often received substandard clothing, shelter, and social services. At the same time, the army presented many black servicemen, particularly those from the rural South, with opportunities unavailable to them as civilians, such as remedial education and basic health care. Military service was also a broadening experience that introduced black men to different people and different parts of the country.